Towards the end of the 19th century, with the advent of the New Liberalism and the innovative

19 April 2023

What’s best at fighting extreme poverty: cash or ultra-poor graduation?

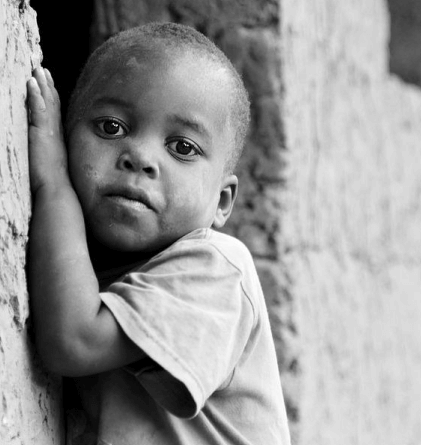

If you want to fight poverty, you probably intuitively feel that the worst-off people are the ones who should be prioritized. As difficult as it is to live on a few bucks a day, someone who’s living on just $1.90 a day clearly has it worse, and it makes sense to think you should try extra hard to help the poorest of the poor. It’s a big moral problem, then, that a lot of anti-poverty programs fail to successfully do that.

That problem has bothered Shameran Abed since the 1990s. Back then, he was working on voguish anti-poverty programs with the international development organization he directs from Bangladesh, known as BRAC. Microfinance was all the rage then, but it was becoming clear that microloans weren’t reaching the poorest households. Nobody wanted to lend to them because who knew if they could pay back the loan? And the poorest households often didn’t want to borrow because they weren’t confident that they could figure out how to turn a profit and repay.

If you want to fight poverty, you probably intuitively feel that the worst-off people are the ones who should be prioritized. As difficult as it is to live on a few bucks a day, someone who’s living on just $1.90 a day clearly has it worse, and it makes sense to think you should try extra hard to help the poorest of the poor. It’s a big moral problem, then, that a lot of anti-poverty programs fail to successfully do that.

That problem has bothered Shameran Abed since the 1990s. Back then, he was working on voguish anti-poverty programs with the international development organization he directs from Bangladesh, known as BRAC. Microfinance was all the rage then, but it was becoming clear that microloans weren’t reaching the poorest households. Nobody wanted to lend to them because who knew if they could pay back the loan? And the poorest households often didn’t want to borrow because they weren’t confident that they could figure out how to turn a profit and repay.

If you want to fight poverty, you probably intuitively feel that the worst-off people are the ones who should be prioritized. As difficult as it is to live on a few bucks a day, someone who’s living on just $1.90 a day clearly has it worse, and it makes sense to think you should try extra hard to help the poorest of the poor. It’s a big moral problem, then, that a lot of anti-poverty programs fail to successfully do that.

That problem has bothered Shameran Abed since the 1990s. Back then, he was working on voguish anti-poverty programs with the international development organization he directs from Bangladesh, known as BRAC. Microfinance was all the rage then, but it was becoming clear that microloans weren’t reaching the poorest households. Nobody wanted to lend to them because who knew if they could pay back the loan? And the poorest households often didn’t want to borrow because they weren’t confident that they could figure out how to turn a profit and repay.

Leave A Comment